The Red Ghost and The United States Camel Corps

Prior to the Civil War, the United States Army experimented with using Camels to transport cargo through the American West. The Camel Corps program would have been considered largely successful if it weren’t for the war. In this episode, we tell the story about how the camels were acquired, tested and the unlikely person who spearheaded the endeavor. Then we chat and play the quiz game with Las Vegas magician Mat Franco!

In Eagle Creek, Arizona in 1883, the legend of the Red Ghost was born. A red-haired beast, 20 to 30 feet-tall, roaming the desert with a devilish-looking ghost rider on its back. The legend went on for 10 years until the truth was discovered. And the truth was almost as fantastical and amazing as the legend. It had started when a couple of ranchers wives saw the beast. While one looked on from her window, the other went outside to see what was going on. She was discovered later, trampled to death. The bushes and trees nearby had snagged some of the beast’s red fur.

Reports of the Red Ghost continued – and they were always the same. A large beast with a ghostly rider. It wasn’t until 1893 that Farmer, Mazoo Hastings shot the beast eating the crops in his field. It was a camel. The leather straps and harness on its back were so tight, they were cutting into the poor animal’s flesh. And sure enough, strapped on the camel’s back was the skeleton of a man, with bits of clothing and hair still blowing in the wind. No one knows exactly why the man was on the camel. He could have been someone trying to escape the desert, desperate for water. It could have been a soldier who tried to ride the beast and failed. But we know where the camel came from. It’s well documented. And that’s where we begin today’s story.

In the Civil War, George H. Crosman was a quartermaster for the Union Army. But before that, he was a soldier in the Indian Wars and fought in Florida. That’s where he was able to see the expansive need for the transportation of cargo just to supply and feed an army in the field. This is where he first came up with the idea that maybe pack animals being used in the Middle East would work well in the United States for transporting materials. The nation was expanding West and the massive amounts of land that needed to be covered was difficult for men and for the animals that were available to them – namely horses. Crossing huge prairies, rivers and difficult mountain terrain seemed like too difficult a task and the intercontinental railroad wouldn’t be completed for decades. He had heard about the usefulness of camels, so he conducted an extensive study and sent his results to Washington. Here’s an excerpt from his report which lays out his reasoning:

“For strength in carrying burdens, for patient endurance of labor, and privation of food, water & rest, and in some respects speed also, the camel and dromedary (as the Arabian camel is called) are unrivaled among animals. The ordinary loads for camels are from seven to nine hundred pounds each, and with these they can travel from thirty to forty miles a day, for many days in succession. They will go without water, and with but little food, for six or eight days, or it is said even longer. Their feet are alike well suited for traversing grassy or sandy plains, or rough, rocky hills and paths, and they require no shoeing…”

His request for Camels fell on deaf ears. No one at the War Department cared to look into it. But as Crosman worked his way up in the Quartermaster department and met Major Henry Wayne, who had also heard about the advantages of camels. Together, they brought up the idea once again. This time, they finally were heard by a young Senator from Mississippi who would later go on to become the President of the Confederacy. Senator Jefferson Davis liked the idea of trying to use camels to help the Army transport cargo and tried for several years to get the War Department to take up the project. After Jefferson Davis was appointed Secretary of War, he finally had enough power for the request to have teeth. The following year, President Franklin Pierce and Congress approved $30,000 for the import of a small amount of camels to the United States for a testing program.

In the summer of 1854, Major Henry Wayne traveled to zoos in London and Paris to talk to animal keepers about camels. Lieutenant David Dixon Porter was the Captain of the ship to bring them over, named the Supply. The two men met up in Italy and traveled to what is modern-day Tunisia to begin their expedition procuring camels. Over the next five months they traveled to Malta, Greece, Turkey and Egypt, gathering animals. It wasn’t easy. Some of the camels were sick and couldn’t be transported. In some regions, they ran into legal problems with export. They ended up with thirty-three animals on-board, a mix of male and female dromedaries and Bactrian camels. A bactrian camel has two humps, while a dromedary has one. It wasn’t until February of 1856 when they started home.

Even the journey home was riddled with problems – mostly severe weather. It took 3 months to return home. During that time, one camel died and two more were born. But the men had spent so much time studying about camels that when they arrived in the U.S., all of the animals were in better health than when they left.

The Camels were unloaded at Indianola, TX – a port that is now a ghost town – and were led 120 miles to San Antonio, then another 60 miles to Camp Verde – northwest of San Antonio. They set up a Middle-Eastern-style corral for the camels and David Dixon Porter left for Egypt to fill his ship with another load of camels. He arrived the next January with 41 more camels.

But how did they fare? How did these American military men adapt to training and using camels in their work?

It was 1857 and through two successful, but difficult trips across the ocean, the United States Army now owned 75 camels corralled at Camp Verde in Texas. It was time to test them. The first test was an easy one. Six camels were tasked with accompanying mules driving a small wagon train to San Antonio. The six camels carried 3,648 pounds of oats. They made the trip in two days and shocked the military leaders who were assessing the trip.

The soldiers hated the camels at first. They smelled. If they got mad, they would bite, or spit. But the biggest problem was that they weren’t horses. And horses were what the men were used to. So they needed to be trained to work with the animals.

The next test of the animals was a practical one. James Buchanan was the new President, and he was having a wagon road built from Fort Defiance, Arizona Territory all the way west to the Colorado River at the California border. It would run the entire width of modern day Arizona – just over 300 miles. The special order for the surveying team was that they were required to bring camels along. It was being used as a real-life test of the usefulness of the animals. The men protested, but complied. They led a large team of camels from Fort Verde, Texas to the starting point of the road surveying expedition in Fort Defiance, then set out west to survey uncharted land. They had initially complained about the camels. But at one point on their journey, they got lost in a canyon. There was no food or water. Nothing for their mules to graze on. The mules started becoming frantic. But the team of camels led the expedition 20 miles away to water, saving the lives of the entire group. After that, it was the camels they relied on to find water. By the time they reached the Colorado river, the camels had been driven over 1200 miles in the middle of the summer. The leader of the expedition had this to say: “I believe at this time I may speak for every man in our party, when I say that there is not one of them who would not prefer the most indifferent of our camels to four of our best mules.”

So why don’t we have Camels in America? The simple answer is because of the Civil War. Remember that one of the most ardent supporters of this program was Jefferson Davis, who became the President of the Confederacy when the South seceded.

Confederate soldiers raided and took over Camp Verde in February of 1861. While most of the Camels were taken out and moved to various other camps, several were captured by the rebel army. They didn’t know how to treat the animals, so they were abused. One was pushed off a cliff. Another was used in service, where it was killed in the Battle of Vicksburg.

The remaining camels that were still being held by the Union Army had their fate decided by Lincoln’s Secretary of War, Edwin M. Stanton. Stanton had no knowledge of the several successful tests of the camels’ usefulness. He didn’t understand, or hadn’t been properly briefed on what these camels could do for his army. He sold them all at auction.

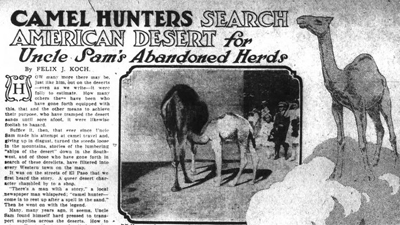

From here, the camels were split up across America – some of the being brought so far as British Columbia. Some were sold to circuses. Some were used in mining operations in the American West. Others were simply turned loose into the wild.

One of the main trainers of the camels, a Greek man from Syria, named Hadij Ali, or colloquially, Hi Jolly – continued working with some of the animals in nearby mining camps. But most of the remaining camels were abandoned.

And this is how it came to be that a camel would be roaming the American Southwest, causing ranchers to panic when they saw a beast that they didn’t recognize. The war had come and gone. The country was in the midst of fighting with reconstruction and severe economic depression. But out west, in Mohave County Arizona, that camel that became known as “The Red Ghost” – the one that Mazzoo Hastings shot on his ranch had been roaming the desert for more than 30 years. It was no ghost. It was the last gasp of a failed program – one of the last pieces of the United States Camel Corps.

Review this podcast at https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/the-internet-says-it-s-true/id1530853589

Bonus episodes and content available at http://Patreon.com/MichaelKent

For a special discount at SCOTTeVEST, FATCO skincare or INBOOZE, visit http://theinternetsaysitstrue.com/deals

https://parkswreckedpod.com

https://www.genxthisiswhy.com

Sources for this episode:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_States_Camel_Corps

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hi_Jolly

https://www.fieldmuseum.org/blog/four-fascinating-finds-rare-book-room

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/whatever-happened-wild-camels-american-west-180956176/

https://armyhistory.org/the-u-s-armys-camel-corps-experiment/