When the Dodgers Killed a Community: Chavez Ravine

Dodger Stadium seats 56,000. It’s the 3rd oldest, and the largest stadium in Major League Baseball. But the story of how – and where – it was built is a difficult tale of the displacement of an ethnic minority community. This episode explores the history of Chavez Ravine and how a Mexican-American community was destroyed in the 1950s. We play the quick quiz with Comedian and Magician Harrison Greenbaum.

It was September of 1980 when 19 year old Mexican pitcher Fernando Valenzuela first took the mound at Dodger Stadium.

He quickly earned his spot – not only as the Dodger’s star pitcher – but as the reason that fans came to games. In 1981, he won both the Rookie of the Year and Cy Young Awards, started the season 8-0 with 5 shutouts and forever changed the fandom of the Los Angeles Dodgers. See, before Fernando, about 10% of the Dodgers’ fan base was Latino. Today, it’s close to half. The pitcher – who had been given the nickname “El Toro” was a huge hit. When the Dodgers traveled to other stadiums around the league, attendance would increase between 5 and 10,000 when he was scheduled to start. Spanish-speaking ushers were hired at Dodger Stadium. Los Angeles was captivated and the Dodgers – an important part of the city’s identity – was finally connecting with the Latino demographic that made up almost 30% of Los Angeles. But under Dodger Stadium, the land holds a painful memory that’s forgotten by most people today. It’s a history of a displaced Mexican-American community.

Chavez Ravine is an L-shaped canyon in Los Angeles. It sits in the hills just north of downtown L.A. Today, it’s made up of Elysian Park, the LAPD Police Academy, Radio Hill Gardens, Angels Point – and taking up most of the land in the middle – Dodger Stadium. It was named for Julian Chavez, who was a Councilman in Los Angeles in the 1830s and 40s. He was the original owner of Chavez Ravine, which was at that time called the Stone Quarry Hills.

The land in Chavez Ravine was never home to affluence or power. In fact, the opposite was true. When the city suffered from the smallpox epidemics in the 1850s and 1880s, it was the site of what they called pest-houses. These were the nicknames given for wards to house Mexican and Chinese-Americans suffering from the disease. At one point, part of the Ravine served as a Jewish Cemetery – the first organized Jewish site in Los Angeles.

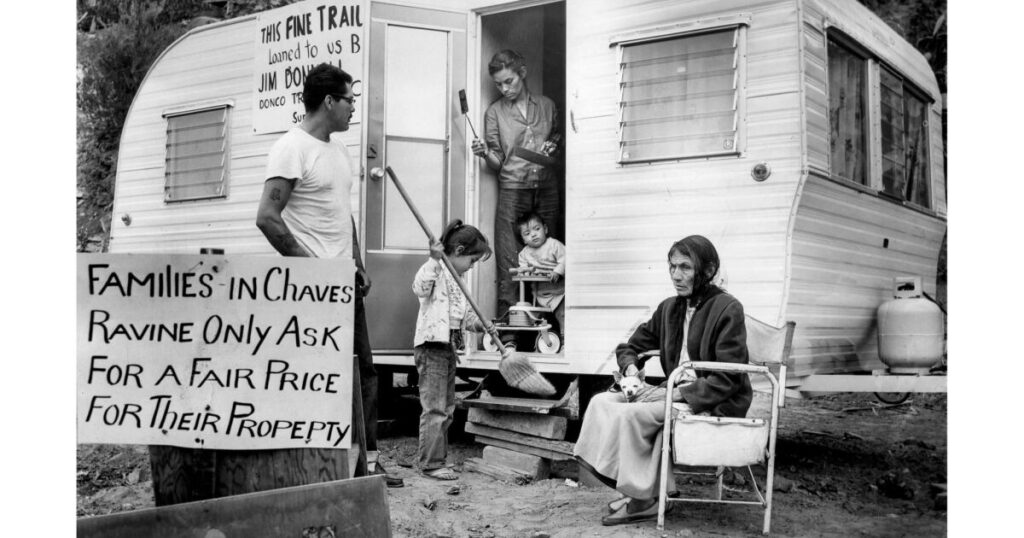

Most of the people who lived in the Ravine were Mexican-Americans. By the 1940s, it was split between the communities of Bishop, La Loma and Palo Verde and because of redlining housing discrimination, these neighborhoods were mostly made up of Mexican-Americans. Most of these neighborhoods were in the hills around the ravine, but there remained a community of houses in the rough terrain that was Chavez Ravine itself. They were a tight-knit community of around 1,500 families within 315 acres. They had their own church, elementary school and grocery store. But it wasn’t an affluent area and the city started labeling this area as “blighted.” “Blighted” is one of this racially charged words that’s most commonly used to describe ethnic minority communities. Around this time, there was also a national push for Public Housing. Harry Truman’s Housing Act of 1949 provided government funds to build housing for those who needed it. In Los Angeles, the L.A. Housing Authority saw Chavez Ravine as the perfect place to build public housing.

Between 1952 and 1953, almost the entire community that lived in the Chavez Ravine was destroyed. The buildings were acquired through eminent domain, some people were paid undervalued amounts for their land and others refused to leave. For those who left, their houses were bulldozed to make room for the public housing. It was to be a planned project community called “Elysian Park Heights.” For the 20-some families who held out and didn’t move, the offers for their land decreased over time in an oppressive tiered buyout scheme.

But this public housing plan came to a screeching halt with the 1953 election of Mayor Norris Paulson. He ran on an Anti-Public Housing platform and gained support from a group known as Citizens Against Socialist Housing. He called such housing projects “un-American” and “communist.” So the public housing project slated for Chavez Ravine was stopped in its tracks. The community had been mostly removed and nothing was in its place. The stipulation of the eminent domain order that was used to remove the people who lived there stated that the city would own the land and it had to be used for public purposes. Several proposals were made – one of them being a new location for the L.A. Zoo.

While his Republican politics led him to kill the possibility of public housing, Norris Paulson’s term as Mayor of L.A. brought a lot of things to the city: The Los Angeles International Airport, the expanded L.A. Harbor…and for the first time, a Major League Baseball team.

It was 1957 and the Brooklyn Dodgers had been dominating Major League Baseball for over a decade. They played at Ebbets Field in Crown Heights.

Ebbets Field was old. It was built in 1913. And it was overused. Not only did the Brooklyn Dodgers play there, but so did 5 different professional football teams and a college team. The Dodgers had won seven pennants in the last 10 years, but couldn’t sell out a game. And Ebbets Field only held 35,000 fans. The problem was it was surrounded by city on all sides. There was no parking. It couldn’t expand. They needed a new home.

Dodgers owner Walter O’Malley chose to move the team to Los Angeles after a lengthy fight with the New York City Building Commissioner who tried to secure land for the team in Queens. But O’Malley heard about a tract of land in Los Angeles that had been cleared for public use. And on June 3, 1958, Los Angeles voters approved a taxpayer referendum on using the land for a baseball stadium. Many L.A. residents opposed it. They didn’t think a “Baseball stadium” was considered “Public Use.” Out of 677,000 votes cast, it passed with a margin of 25,000 votes. The stadium would be built. It would seat 56,000 and the entire land acquisition would be 352 acres.

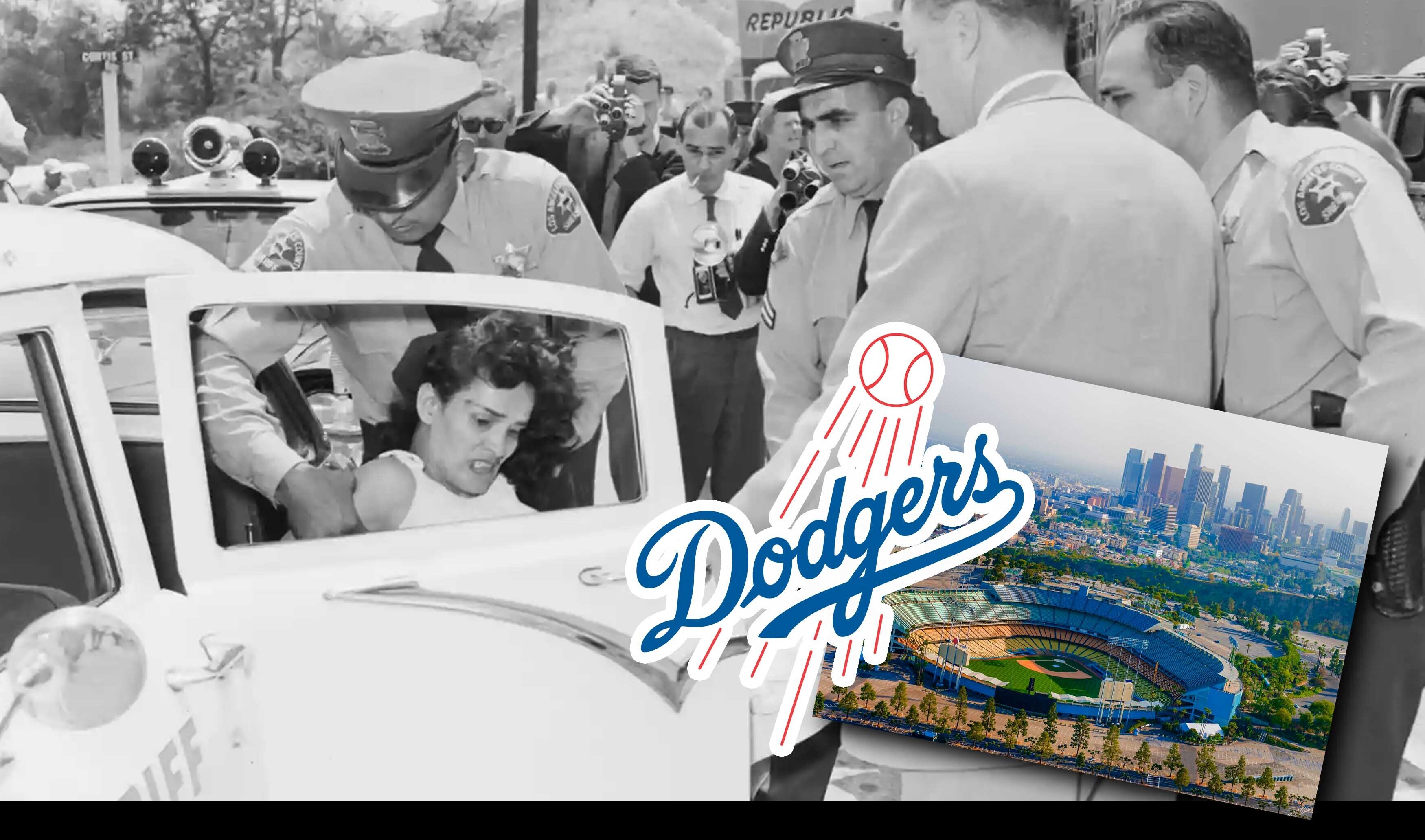

One year later, the Arechiga family was throwing rocks at police. Remember there were still a small number of residents of Chavez Ravine who refused to move. But at this point, the L.A. County Sheriff’s Department had no choice. They had to clear the land. The Arechiga family had lived there for generations, but now the Sheriff’s deputies had come to forcibly remove them. It was too late to accept payment for their land. It was no longer being offered. Elderly Manuel and Abrana Arechiga watched as police first carried away their adult daughter, Aurora Vargas. She was a war widow living in the home with her parents. 72-year old Abrana threw rocks at the officers. It was a two-hour ordeal. All the residents were removed. Vargas was briefly put in jail for resisting arrest. Only minutes later, bulldozers flattened their house.

They lived in tents on the area of their land to protest, and for a short time – gained some support from the citizens of Los Angeles. But when construction started on Dodger Stadium the next month, public support for the displaced families waned. 8 million cubic yards of earth were moved to fill in and flatten out the space in the middle of the ravine. The elementary school wasn’t even removed. They just buried it. It’s still there today, underneath the northwest parking lot.

The people and the families of those who were removed call themselves Los Desterrados (the uprooted). It’s probably important at this point to talk about the title of this episode. It wasn’t really the Dodgers who killed their community. The Dodgers just sealed its fate. The thing that killed the community was the way that society sees poor or minority neighborhoods. It was a target. When the homes of Chavez Ravine were wiped out, a few of the structures that weren’t demolished were sold to Universal Studios. One of them appears as the house of Atticus Finch in the 1962 film To Kill a Mockingbird.

Dodger Stadium was built with private money, but it was a city project. The stadium revitalized downtown Los Angeles. It was the first major upgrade to downtown L.A. in decades. After seeing businesses downtown start to disappear, it began to bring excitement and commerce to the area. If you look at that area today, it’s buzzing with luxury apartments, expensive restaurants, museums and concert venues. Dodger Stadium is a beautiful ballpark. At 56,000, it’s the largest stadium in Major League Baseball and definitely has brought some good to the area. But the stadium – home to a team with a 50% spanish-speaking fan base – has a dark past. And while it was news at the time, most people today don’t realize the pain and anguish that occurred to create the stadium as we know it today.

Review this podcast at https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/the-internet-says-it-s-true/id1530853589

Bonus episodes and content available at http://Patreon.com/MichaelKent

For a special discount at SCOTTeVEST, or FATCO skincare, visit http://theinternetsaysitstrue.com/deals

Sources for this episode:

https://americanhistory.si.edu/pleibol/game-changers/big-leagues-destroyed-barrio

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Chavez_Ravine

https://www.zinnedproject.org/news/tdih/chavez-ravine-evictions/

https://www.npr.org/sections/codeswitch/2017/10/31/561246946/remembering-the-communities-buried-under-center-field

https://laist.com/news/la-history/dodger-stadium-chavez-ravine-battle

https://www.nytimes.com/1957/12/07/archives/dodgers-still-bank-on-home-in-los-angeles-despite-snags-harried.html

https://www.latimes.com/sports/dodgers/story/2021-04-12/fernando-valenzuela-dodgers-baseball-hall-fame

https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2017/apr/12/dodger-baseball-stadium-shaped-la-and-revealed-its-divisions