The Bouba/Kiki Effect & The Shape of Words

Researchers have found that almost 90% of the time, subjects will associate nonsense words “bouba” and “kiki” with nonsense drawings. But why? In this episode, we discuss the strange linguistic phenomenon of sound symbolism and discuss how sometimes, the sounds of words themselves can carry meaning. Then we chat with Social Psychologist, Dr. Andy Luttrell of the Opinion Science podcast.

It is generally understood by those who study language that there is no relationship between the way a word sounds and the meaning of a word. In other words, listening to a word usually gives you no clue as to what the word means. But, as with any rule, there are exceptions. One of them is what’s known as onomatopoeia. These are words that are specifically created to mimic a sound. And usually the examples that are given are comic book words – “Pow!” “Splat” and “Bam!” These words are supposed to sound like the sound they’re describing.

There are also some unusual onomatopoeia words, like blimp, which is supposed to be the sound that’s made when you thump a balloon. Bumblebee is supposed to be the sound of a bee. That’s how the sound was described in middle english in the 1520s. Here’s an interesting note. Another dialect word for bumblebee was…Dumbledore. Chatter is an onomatopoeia word for the sound of teeth hitting together. And another unusual one is the word “Cliche.” It’s meant to mimic the sound of a printing press. So when something is done over and over, it’s cliche.

So – even in the case of the non-obvious ones, we expect onomatopoeia words to sort of have a sound that is related to the meaning. But another surprising instance of word forms having a connection to their meaning is in this weird phenomenon that was first discovered by a Georgian Psychologist Dimitri Uznadze in 1924, and expanded upon in a 1929 book by German American Wolgang Köhler. It’s the idea of iconicity – the ability for a word meaning to have a picture or shape automatically associated with it.

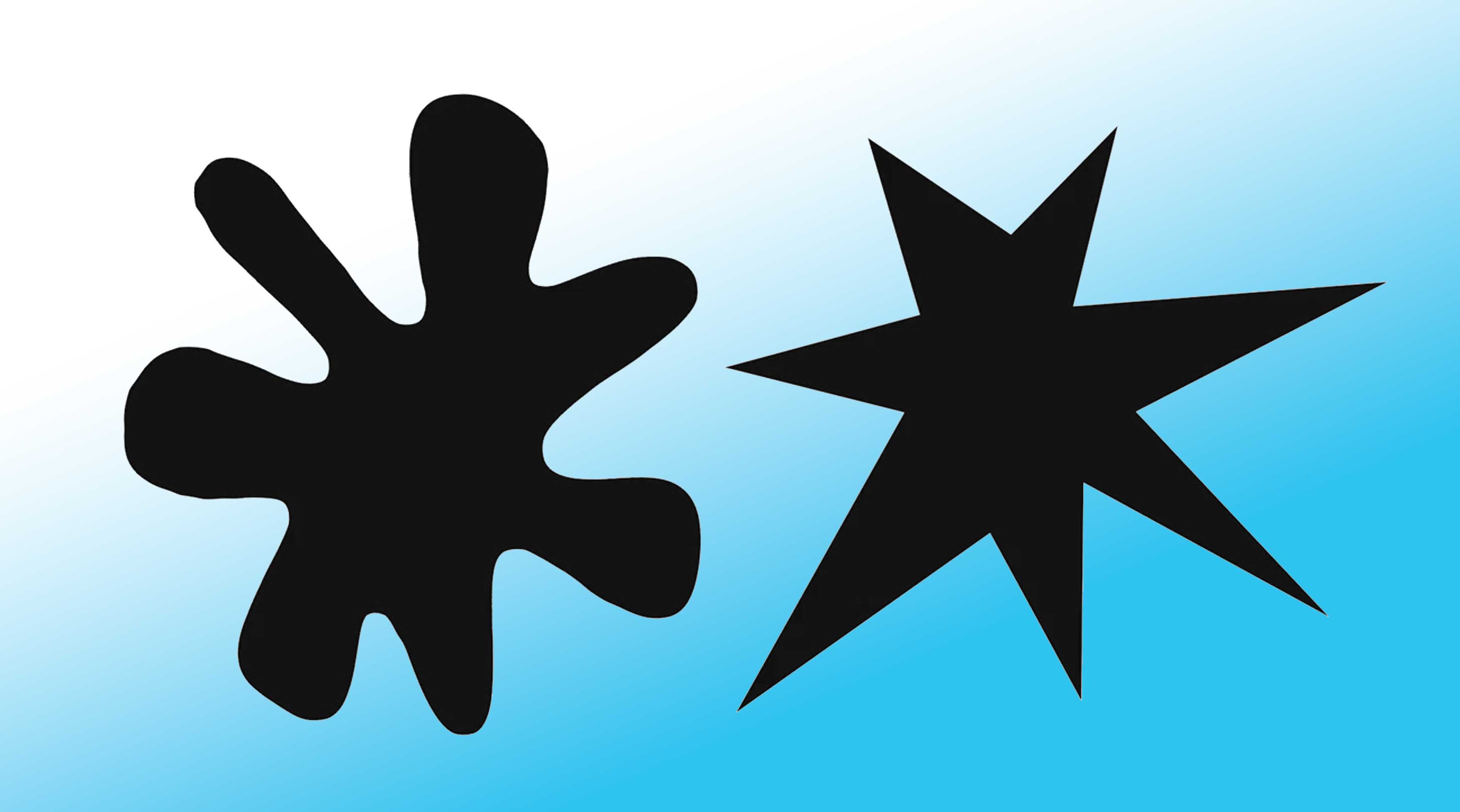

A group of people were shown two nonsense words and two nonsense shapes. And they were asked which shape was associated with which word. In Köhler’s study, the words were “Maluma” and “Takete.” Then the two shapes that participants were shown were very different from each other. One was an amoeba like blob with rounded edges, sort of like a puddle of liquid. The other was a shape with jagged edges and points – like a starburst. In his book “Gestalt Psychology,” Köhler found that most people associated the word “Takete” with the jagged shape, while associating the word “Maluma” with the rounded amoeba shape.

So that brings us to the most popular version of this study – and the study for which the phenomenon is named. Two researchers in 2001, Ramachandran and Hubbard were studying Synaesthesia, the phenomenon where to certain people, words are associated with colors – and they redid the original 1929 study, this time with the nonsense words Bouba and Kiki. They used the original spiky and amoeba like shapes and get this – 89% of all people who took part in the study all associated bouba with the more rounded shape and kiki with the spiky shape, despite these words having no meaning. And it wasn’t just English speakers – this was repeated with speakers of all languages – and with very few exceptions – the effect held true. Some of those exceptions were in the case of people from Papua New Guinea and Nepal. They didn’t associate the words with the shapes in the same way at all. Their results were completely random. It’s thought that it’s because in those areas, where the languages of Songe and Syuba are spoken, respectively, the words kiki and bouba aren’t words that could actually exist in their languages. Another interesting diversion from the effect is in the case of children with autism, who only associated them according to the effect 56% of the time.

So why is this happening? Why are we able to associate a nonsense word with a nonsense shape if there’s no connection between the way a word is formed and its meaning?

When I first heard about the Bouba/Kiki Effect, I didn’t get it. I thought, yeah. Of course Bouba is the rounded one and Kiki is the pointy one. Why wouldn’t it be? You may be thinking the same thing. What’s the big deal. The rounded form goes with Bouba. But ask yourself why. What is it that tells you that the word Kiki is the pointy shape?

Well it seems like humans tend to associate round shapes with voiced plosives, nasals and back vowels, which are linguistic terms for vowels like O and U – vowels that take up more space in your mouth. And voiced plosives are things like B – the letter B requires you to vibrate your voicebox to create. Whereas if you try to make an B but don’t voice it, it becomes a P sound. The technical term for a B sound is a voiced bilabial plosive. So we associate those types of sound with rounder shapes.

The jagged, sharp shapes tend to be associated with front vowels and unvoiced plosives. So a front vowel would be like e, I, shorter sounds and an unvoiced plosive would be like the p we talked about, or a k. A k sound is an unvoiced version of G. Try that – if you make a k sound, but vibrate your vocal chords, now you’re saying the G sound.

Aleksandra Cwiek has a PhD in Linguistics and studies iconicity and sound symbolism. She conducted one of the largest-scale experiments studying the Bouba/Kiki effect, testing speakers from 25 different languages. She says “there are things that connect us as humans that are deep in our cognition, deep in our nature,” and this goes back to when the words we use are created. An example of this is when we’re talking about the sky, we use a higher pitch voice or talking about something way down low, we use a lower pitch voice. This is just part of how we communicate with each other. It’s in our nature to create sounds that convey meaning. This is essentially what iconicity is. Some call this cross modal correspondence, or sound symbolism – but the basic idea is that there is more to a word than its spelling. It’s spelling may not carry meaning, but the sounds that make up that spelling very well might. Consider the example I just gave. The word low has those back vowels and the word sky and high have those front vowels.

Part of the explanation about how this works is the shape of the letters used. Bouba is a word with rounded letters and curves that could be associated with the rounded shape. The Ks in “kiki” could be associated as being more jagged. Or we could talk about the rounded shape your mouth makes when you make these sounds. Maybe the round mouth used in Os and Us could make people think of the rounded shape.

So back to the Bouba/Kiki experiment, Dr. Aleksandra Cwiek also found some instances where the effect didn’t work as well. Speakers of Turkish have a word similar to kiki and it means cute. It’s used for things like babies. So of course, that overrides the effect because that cultural association is stronger than the one based on the sounds alone. So Turkish speakers didn’t always associate kiki with a sharp pointy shape because they were thinking of cute round fat little babies. And in Romania, they have a word that sounds like bouba. It means wound. So they were probably associating bouba with pain, and that was more likely associated with the sharpness of the jagged shape for those speakers.

In Japanese, many of the words have this sort of sound association. They’re called ideophones. It’s like a language made up of lots of onomatopoeia.

I personally find this stuff fascinating. I hope you do too. The point of this podcast is to give you stories that you can tell the people around you. To understand the world and our history a little better. And now, next time you get together with friends, draw these two shapes on a napkin, give them the two nonsense words and conduct your own version of this experiment. Then you can tell them all about the bouba/kiki effect.

Review this podcast at https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/the-internet-says-it-s-true/id1530853589

Bonus episodes and content available at http://Patreon.com/MichaelKent

For a special discount at SCOTTeVEST, visit http://theinternetsaysitstrue.com/deals