Dr. Mary Edwards Walker: Defying Gender Norms During the Civil War

Mary Edwards Walker lived a life so incredible that we had to cut a lot of her accomplishments out to fit into this podcast. But her story is one of perseverance, strength and very definition of a person marching to the beat of their own drum. In this episode, we talk about Mary Edwards Walker’s efforts to treat the injured during the American Civil War, then we play the quiz with Writer Joe Janes!

I personally consider Andrew Johnson to be one of the worst, if not the single worst President the United States has ever had. His reluctance to carry through with Lincoln’s plan for reconstruction created a ripple effect that we still see today, almost 160 years later. He opposed the Freedmen’s Bureau, the Civil Rights Act of 1866, and the 14th Amendment. He wasn’t just a racist, he was an institutional racist who made a real-world negative impact on the lives of future generations of Black Americans. Which is why I was shocked to see how he turns up in today’s story.

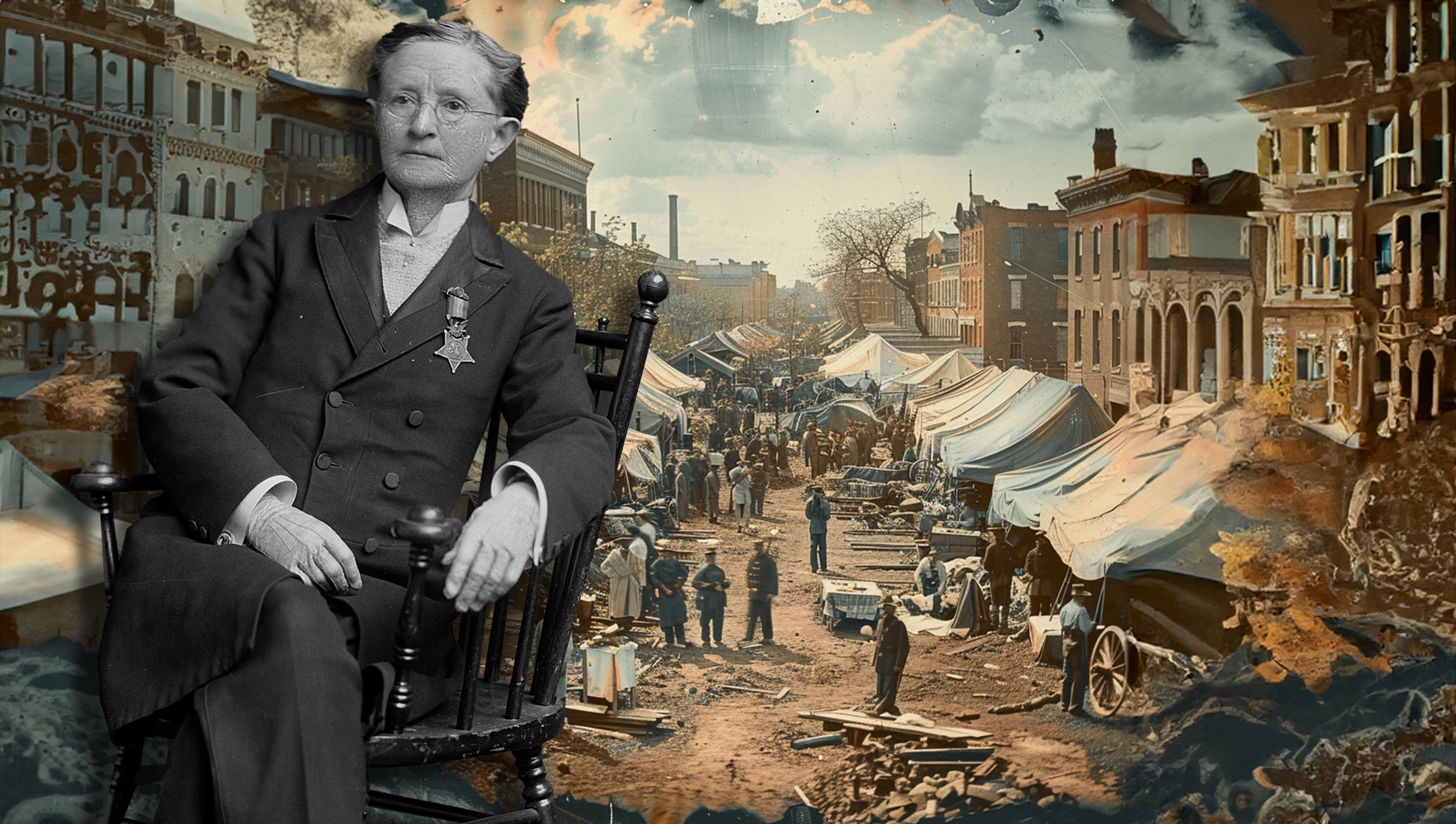

Mary Edwards Walker was born in 1832 in Oswego, New York. Her dad, Alvah was a real progressive thinker. He didn’t take the traditional stance that women should merely stay home and raise children. He thought women should be well-educated and pursue roles in the professional workplace. He was into health and instilled a lot of his beliefs into his daughter Mary. They were prohibitionists, believing that alcohol and tobacco were horrible for health. Alva also believed that many of the women’s fashion trends of the time were unhealthy. And he was right. It was the fashion for women to wear corsets, which had the potential to cause internal organ damage. He believed that everyone should wear loose-fitting clothing and forbade his daughters to wear corsets. As Mary grew up, she found that the most comfortable clothes for her were those worn by men. Her entire wardrobe consisted of loose fitting trousers and men’s suits. On a rare occasion when she did wear more traditional women’s clothing, it would be a simple, loose-fitting floor-length black dress.

Mary was influenced by her father’s proclivity for health fads and became interested in studying Medicine. In 1853, at the age of 21, Mary was accepted as the only female in her class at Syracuse Medical College. And this was a new and rare thing. There was a shortage of doctors as America was expanding West and some medical schools had just recently started accepting women. And being that she didn’t act like most females their age, she was ridiculed by fellow students. Here’s this women dressed in men’s clothing who was outspoken and stood up for herself.

After graduating with honors from Syracuse Medical College, Mary moved here to Columbus, OH to set up a medical practice that failed because people wouldn’t trust a female doctor. She left because of that, but also to be married to a man she had met in college. She wore a men’s suit to the wedding, refused to include the line “to honor and obey” in the ceremony, and kept her own name. I can’t help but mention here that in Walker’s formative years in high school, Elizabeth Cady Stanton’s efforts in the American Feminist Movement were taking place in Seneca Falls – not far from Mary in upstate New York. So while I didn’t see that she ever attended the Seneca Falls Convention – she would have been 16 at the time – I think it’s likely that she was positively influenced by the feminist movement. So after being married, the two set up a practice in Rome, New York, which also failed and they ended up getting a divorce a few years later, when her husband was unfaithful.

She briefly went back to school, first to Bowen Collegiate Institute and then the New York Hydropathic and Physiological School. Interesting story about her time at Bowen. She joined the debate team and they didn’t want a girl on the team, so they made her resign. She refused to resign, so the college suspended her. And her entire life was filled with stories just like that.

Mary left New York Hydropathic and Physiological School in 1862 as the nation was descending into the chaos of the Civil War – and there was a new goal in her sights. She wanted to be an Army field surgeon to help in the Union war effort. She had already made her name as an influential woman. She often contributed articles to feminist publications like Sybil, which was a publication by Lydia Sayer Hasbrouck. She would write about topics like the way women dressed, encouraging other women to wear more comfortable and pragmatic clothing. She took this new goal of helping with the war effort seriously. She traveled to Washington D.C. and volunteered her medical services. She ended up being an assistant to Dr. JN Green, but she really wanted to be a commissioned Army surgeon. Dr. Green lobbied for her to be accepted by the military, but they refused, keeping her as a civilian volunteer.

But her Civil War efforts didn’t only take place in a hospital in Washington.

When Mary Edwards Walker arrived in Washington wearing men’s clothing, she wanted to be a part of the United States Army. The Surgeon General refused, but allowed her to work as a civilian assistant to surgeons. She was doing amazing work, and eventually carried just as much job responsibility as her male counterparts in the hospital. She began a relentless letter-writing campaign to Congressmen and Senators to plead her case, but was continually refused.

In the meantime, the work continued. Walker was, by this point actually traveling to battlefields and setting up makeshift field hospitals in abandoned barns and warehouses. She was treating as many wounded men as possible and became an incredibly important field surgeon – but still a volunteer civilian surgeon not getting paid. She was even helping to instill better practices for people treating the wounded, like teaching the proper way to carry injured men on a stretcher and arguing against how frequently amputations were being carried out. After the second Battle of Bull Run in Manassas, she actually showed up on the Battlefield in uniform. A uniform that she had created herself – a blue officer’s coat, trousers with a gold stripe, a blue hat with gold cord and a green sash to indicate that she was a medic. General Ambrose Burnside was shocked to see her show up with her own uniform and allowed her to treat his wounded – six railroad cars worth – on their evacuation back to Washington. And on her return, she was denied a commission once again.

This time, she wrote to War Secretary Edwin Stanton. She pitched an idea to Stanton that she would create a regiment of convicts and jailed men to help her in her efforts to treat the wounded. They would be called “Walker’s Patriots.” Stanton denied her offer.

At this point, she traveled all the way down to Tennessee to assist General George Thomas’s Army of the Cumberland. She once again petitioned to be commissioned and throughout her later life, claimed that General Thomas granted her that commission, but there’s no written evidence to support that. According to her biographer, Charles McCool Snyder, General Thomas’s director of the medical staff fought against the idea of a woman surgeon. He said it was a “medical monstrosity” and called for an Army Medical Board review of Walker’s qualifications. It was there in Tennessee that Mary Edwards Walker offered to become a spy for the Union. She was granted permission and set off to enter into enemy territory, actually making her way to treat wounded men behind enemy lines. As she was assisting a Confederate surgeon in an amputation, somehow she was found out and captured as a Union spy.

That’s how Mary Edwards Water ended up on a train 700 miles away to the Confederate Capital of Richmond. She was locked up in horrendous conditions at Castle Thunder, the name of an old warehouse in Richmond used as a makeshift POW camp. She received a pencil and paper and began writing more letters, begging for her exchange out of the prison. After 4 months in rat-infested Castle Thunder, she was finally granted exchange. The man exchanged for her was Major Lightfoot, a Confederate Doctor being held by Union troops. That prisoner exchange happened in 1864, near the end of the war.

Mary’s relentless letter-writing continued after the war. She continued lobbying anyone and everyone she could to argue that she be commissioned, compensated and recognized for her war efforts in those years after the war. She had sacrificed a great deal to help the Union and wanted a pension like her male counterparts. And she argued that she should be given the rank of Major, since they exchanged a Major for her. This time her letters made it to the President himself, Andrew Johnson, who actually had a desire to recognize Walker for what she had done.

In 1866, President Johnson told her that there was no legal way to commission her, but he did agree to grant her something huge: The Medal of Honor for Meritorious Services. In the citation that accompanied the Medal of Honor, it was never described what services she had done.

In that same year, she was surrounded by a mob of men in New York City, angry at her for the way she appeared. She called for a shopkeeper to call the police, but the police arrested her when she defiantly refused to identify herself. She took action against the arresting officer and won. In the trial, it was stated that Walker could dress however she wanted.

While she was proud to receive the Medal of Honor – many of her photos show her wearing it pinned to her chest – she didn’t give up her campaign to receive a military pension. And after 10 years of letter writing, she was finally granted an $8.50 a month pension, then it was raised to $20 a month.

In 1917, Congress decided that Medal of Honor recipients couldn’t be awarded to non-combatants. So Mary, along with 900 others, had her Medal of Honor stripped away from her just before dying in 1919 at the age of 86. This injustice was finally rectified 60 years later when her family petitioned President Jimmy Carter. In 1977, her Medal of Honor was posthumously restored.

When I read this story, I see someone who fought her entire life for what she wanted. She never relented and was faced with adversity every step of the way. Just for being herself and doing what she was born to do – help people. At the time of recording this in 2024, there have been 3,517 Medal of Honor recipients. 3,516 of them have been men. To this day, Mary Edwards Walker is the only female Medal of Honor recipient. The Internet Says it’s True.

Review this podcast at https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/the-internet-says-it-s-true/id1530853589

Bonus episodes and content available at http://Patreon.com/MichaelKent

For special discounts and links to our sponsors, visit http://theinternetsaysitstrue.com/deals